Book review: Smoke Gets In Your Eyes by Caitlin Doughty

Caitlin Doughty, graduate in medieval history and author of a sunny thesis entitled The Suppression of Demonic Births in Late Medieval Witchcraft Theory, rejects a promising career in academia in favour of one as a corpse handler and incinerator of the dead.

Anticipating bewilderment she asks, rhetorically, “So, really, what was a nice girl like me working at a ghastly ol’ crematory like Westwind?” And she goes on to tell us what drew her to it. She describes a traumatic childhood trigger event. I won’t reveal what it was, of course; you need to read Smoke Gets In Your Eyes for yourself. Her theory is that she dispelled the consequent denial that insulated her from the traumatic event by confronting her fears and getting on down with corpses. As a result of this self-prescribed and gruelling CBT she is now at peace with the “stillness and perfection of death”.

More than that, Doughty is now the world’s leading cheerleader for death: “Death might appear to destroy the meaning in our lives,” she says, “but in fact it is the very source of our creativity.” This is just one of many debatable assertions she makes in this book. Death may inspire urgency and thereby rouse latent creativity, but it is doubtful whether it can put in what God left out.

Doughty is the leader of a clever, charismatic and acclaimed corpse cult, the Order of the Good Death, “a group of funeral industry professionals, academics, and artists exploring ways to prepare a death phobic culture for their inevitable mortality.” You’ve seen the Ask A Mortician video series — you have, haven’t you? She’s sassy, funny, outrageous and very likeable. She’s a brilliant performer. She spills and splashes behind-the-scenes secrets with a mischievous glee that appals and infuriates industry insiders, who firmly believe that there are Things It’s Best We Don’t Know. To this day, despite a great and growing following, she remains shunned by the National Funeral Directors Association. Her preparedness to bring down, in Biblical abundance, the murderous fear and loathing of old school funeral people takes guts. She’s outrageous because she’s also passionately seriousness.

Like so many progressives, Doughty is essentially retrogressive — in a positive way. Her prescription for the way things are is to get back to doing them the way we did. Nowadays, when someone dies, we call the undertaker and have them disappeared. This, reckons Doughty, is a symptom of a “vast mortality cover-up … society’s structural denial of death … There has never been a time in the history of the world when a culture has broken so completely with traditional methods of body disposition and beliefs surrounding mortality.”

The way to restore society to emotional and psychological health, Doughty believes, is to engage with the event and get hands-on with the corpse. She believes that “more families would choose to take responsibility for their own dead if they knew that it was a possibility.”

This is what working in a crematory teaches her: “Westwind Cremation & Burial changed my understanding of death. Less than a year after donning my corpse-colored glasses, I went from thinking it was strange that we don’t see dead bodies any more to believing their absence was a root cause of problems in the modern world. Corpses keep the living tethered to reality.”

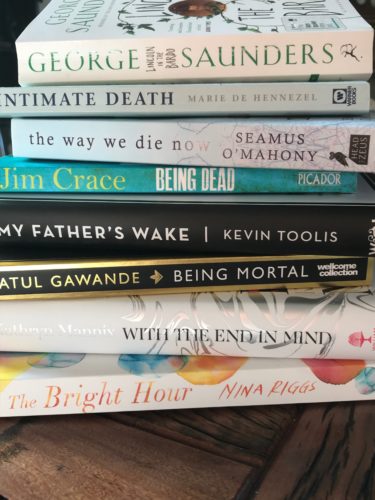

I’m not so sure. I have in mind David Clark’s 1982 paper, Death in Staithes. The older inhabitants of Staithes, a fishing village on the east coast of Yorkshire, could easily recall the way things used to be: “When a person passed away the first thing they did was go for the board – the lying-out board,” which was kept by the village joiner. The lying-out itself was supervised by women qualified by skill and experience. These same villagers had lived through the commodification of death and the arrival of the Co-operative. To them the hands-on past is no paradise lost and they display no desire to return to it.

I question Doughty’s assertion that we suffer from “structural denial of death.” If we were to think about death some more, would it really do us any good? Yes, she says: “I don’t just pretend to love death. I really do love death. I bet you would too if you got to know him.” Elsewhere, she writes: “Accepting death doesn’t mean that you won’t be devastated when someone you love dies. It means you will be able to focus on your grief, unburdened by the bigger existential questions like ‘Why do people die?'”

Philip Larkin felt sort of the same until he hit 50. In Julian Barnes’ words, “our national connoisseur of mortal terror … died in a hospital in Hull. A friend, visiting him the day before, said, ‘If Philip hadn’t been drugged, he would have been raving. He was that frightened.’” Pretty much the same can be said about the death of another connoisseur, Sherwin Nuland, the man who wrote with spooky prescience “I have not seen much dignity in the process by which we die.” He was that frightened, too.

“Let us … reclaim our mortality,” exhorts Doughty headily. But does the dearth of corpses in our lives really distance us from death? Death was big in the lives of everyone in the past because people died at any age. They don’t do that so much now, they mostly die old, and that’s less tragic, less sensational. But death is arguably bigger in our lives than ever before because the dying spend so bloody long about it. There can be very few children who are not acquainted with a tottering, muttering relative, and very few adults who do not spend years despairingly caring for dementing, degenerating parents. They are in no doubt about what their parents are doing: they are dying a modern death, a slow and beastly death. That’s why there’s such an intense national conversation in so many countries about assisted suicide — come on, how mortality aware is that? Far from being a time of death denial, the present age has focussed our attention on mortality at least as urgently as any other because the distressing dilapidation of legions of almost-corpses starkly and terrifyingly prefigures our own end times, leaving us in no doubt that the home straight is going to be unutterably horrible. If we don’t feel we have much to learn from corpses, we learn as much as we feel we need from the living dead (ever seen a stroke ward?) and from self-deliverers like Brittany Maynard. They teach us the allure of Nembutal. We talk about this. A lot.

What people believe also plays its part in modern attitudes. Religious and spiritual-but-not-religious people are, pretty much all of them, dualists. There’s a soul and there’s a body. It’s a belief reinforced by the appearance of any corpse they have ever seen. Gape-jawed and evacuated of all vitality, a corpse speaks of the absence of self. Whoever it once embodied has gone. The corpse is not the person, so what value is there to be gained from cosseting it? This isn’t a new thing. Radical Protestantism has always taught it. Calvinist settlers in America became very careless of the ‘dignity’ of their soul-less dead and drifted into just hauling them into the forest or pushing them into rivers. In some places it got so bad that neighbours were appointed to oversee next door’s disposal arrangements and held responsible for making sure things were done properly. For these settlers, direct cremation would have been a godsend.

If I take issue with Doughty’s thesis, it is because someone’s got to. For Doughty, the contemplation of the corpse is “the beginning of wisdom.” If you are inclined to believe that, she says, “Don’t let anyone ever tell you you are ‘sick’ or ‘morbid’ or ‘deviant.’”

What does morbid mean, exactly? It is Doughty herself who has pointed out that it has no antonym. Yes, what is the word for a healthy interest in death and dying? How does it express itself? Doughty and her fellow members of the Order of the Good Death express their wisdom exotically, sharing delight in much that others would regard as macabre — transi tombs, taxidermy, mortabilia and of all sorts. All a bit goth for my taste; I think there’s more than a dash of innate morbidity here. It would be idiotic to question the charisma of the cause, because it has attracted a huge worldwide following. How does it play to Mr and Mrs Everyday-Person? It remains to be seen. All I can say is that, speaking as a detached and jaded dullwit, after 6 years of hanging out with funeral people and their charges I remain unconvinced of the value of the corpse in death rituals, and while I acknowledge matter-of-factly the inevitability of death, I hate it as much as I ever did.

If by now you need some remission from my grinding and joyless pessimism, you need to buy this book. It it touches all the right bases — funny, shocking, sad, wise. Above all, it is full of hope and purpose. It is also highly readable. It was only when I re-read it that I became aware just how beautifully constructed it is. This is the work of a highly intelligent person who has got the inspiration-perspiration balance right (1:99). What she has to say is the product of experience, a lot of it penitential. She has captured the zeitgeist. This is a manifesto for today.

ECSTASY OF DECAY №1: Your Mortician from Angeline Gragasin on Vimeo.